“What’s your major? What year are you? What dorm do you live in? Standard questions when making friends in college. But as I cross an old stone bridge and meet a dozen travelers from Barcelona, I’m met with a different set of questions that I will hear over and over again in the coming week: “Are you doing the road to Santiago?” “How many days will you be walking?” “Where are you staying?”

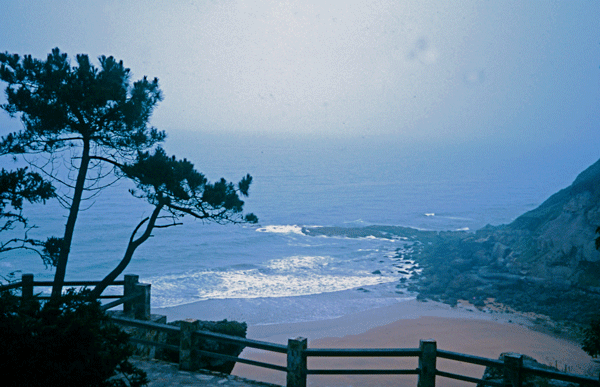

On the scallop shell-marked trail of a legendary medieval pilgrimage route in the province of Asturias in the northwestern corner of Spain, I’m catapulted into a land of sensory delights. Some forty miles from the capital, Oviedo, I depart Caravia Alta and get into a rhythm, ambling down farmer’s tracks cut through swaths of verdant fields. The only sound is my boots scuffing the dirt which becomes almost meditative. Once in awhile the clanging of cowbells reverberates through the air, calling my attention to grazing cattle. The verdancy is interrupted by the tumbling waters of the Cantabrian Sea with its strip of golden beaches. Gulls soar overhead as I wander beside Playa de Caravias, a wide sandy stretch that’s populated only by three fishermen standing in the surf, a woman on a brightly hued blanket, and a jogger.

I’m not trekking along the much more popular French route, favoring instead, paths that meander along the coast and interior to Santiago de Compostela (though I’m only tackling a one week portion of the lengthy trail). This route — the oldest of the Way of St. James — was the one pilgrims navigated during the first millennium when Asturias was the only region of Spain that remained unconquered by the Moors (no wonder considering the rugged terrain) and it was considered the safest. In the 9th century, King Alfonso II had also made this pilgrimage from Oviedo through the interior to Santiago de Compostela. But 200 years later the court moved to the province of Leon to the south, and pilgrims turned to the Roman road that became known as the French Way of St. James. When a French monk, Aymeric Picaud, penned a guide of that route, it became the preferred one and superseded the other through Asturias until 1990 when the government restored the legendary scallop shells – the metaphoric symbol of the St. James’ Way – along the original route.

In the hamlet of La Isla, I stop to buy several juicy peaches. Navigating through a rich landscape of apple orchards as well as farms growing tomatoes and corn, I notice a signature structure of the Asturian countryside, hórreos (or granaries), which are often constructed of wood and sit atop stilts. At the edge of a dense conifer forest that skirts Playa de la Griaga sits a curious plaque describing Asturias Jurisica. Struggling to read the Spanish, I realize it’s all about dinosaurs and fossils. Examining the ground, I see the ancient dinosaur footprints imbedded in the rocks that border the forest. Asturias is full of discoveries.

I’m alone but never lonely. The villagers along my path are so well acquainted with pilgrims that well wishes follow me wherever I go. In the hamlet of Colunga, I pass several rotund middle-aged women, each wearing long print dresses, relaxing in their yards. One shouts “Are you on the road to Santiago?” When she gets to the question about where I live — New York City — they exchange looks of surprise. “You’ve come so far,” the other says. And then, when it’s time to move on, they shout “Bien viaje” in unison.

Pis, Perus, Pernús and other hamlets are defined by lone churches, well-watered fields and dense clusters of oak, walnut, beech and other trees. It looks like Spain’s little Eden here. Strolling to the doors of a pre-Romanesque church in Priesca, I find it locked, but the housekeeper opens it and gives me a tour, pointing out the remnants of colorful frescoes adorning the walls. The churchyard makes for an idyllic picnic spot where I lunch on Manchego cheese, apples and bread. It’s from here that I spy the most impressive valley so far, painted like a quilt stitched of emerald and mint.

Dense clouds and a blanket of mist that cowls over the valleys are typical in Asturias. I stop for the night at the Monastery Santa Maria de Valdedios. I find my room with a cast iron balustrade encircling a petite balcony, cozy. French windows look out to the main church as well as to the adjacent San Salvador de Valdedios, a 9th century pre-Romanesque one that offers a tour of the interior. Though it’s given in Spanish, it’s worth it just to see the wall niches near the front door where pilgrims once took shelter. Inside there are the remains of frescoes on the ceiling, walls and archway.

The following day, I become intrigued by signs for “El Melain — Se Vende” along with hand drawn sketches of berries near the hamlet of Sariego. Following them, I pick up plastic containers and a tray and amble through row upon row of blueberry, raspberry and blackberry bushes. I can’t keep my hands off these plump little fruits, sampling handfuls as I gather them in the quart containers. The overall-clad owner tells me about several varieties of homemade ice cream, all made with freshly picked berries. I manage to devour several pints of the rich, creamy blueberry before continuing on the Camino. Clearly, unlike the pilgrims of the Middle Ages who tackled this route, I’m taking a much more leisurely and hedonistic approach.

With a full belly my pace becomes slowed and I soon find myself chatting with a farmer sitting atop a tractor to verify that I haven’t strayed from the path to my next accommodation, the Hotel Rural El Nogal. My search ends at a blooming garden with chaises longues and a canopied swing set amidst hedges, bougainvillea and apple trees. In a dining room decorated with images reflecting Asturian culture – women weaving and others in native dress, Puri, the energetic and enthusiastic owner, serves grilled mellusa fish with locally-sourced tomatoes as we discuss the sustainable Asturian cuisine. She signals a young man to pour me some fermented cider (made the traditional way from local apples) and he does so with one arm, raising the bottle high over his head and allowing the cider to stream into my tiny glass, a technique that aerates it. The tart, slightly fizzy cider is served warm. A small glass of sweet wine and slices of Cabrales cheese and thick, creamy yogurt top off the meal.

Heading toward the Golf Course La Lorea, I follow Ruta del Río Nora, a damp trail coursing beside the River Nora. When I hear rustling I jump, but it simply turns out to be a couple of grey-haired men with a large group of dogs. They’re hunting for truffles and have no time to chat. With their dogs sniffing through the foliage, they hurry on their way. I’m hoping to see some wildlife such as wild boar which is listed on the many signs along the path. At El Hórreo, a restaurant that, appropriately, sits beside eight of these eponymous structures, I order a jamon y queso (ham and cheese) bocadillo to take-away, and picnic at Parque del Cabo San Lorenzo, a prime spot to watch paragliders launching from the grassy area atop the cliffs. As I take my last few bites, one cruises directly above my head.

My journey ends in Gijón, a bustling port and summer resort along the scenic coastal curve. Across the street from a large statue of King Philip III sitting astride his horse is Confraternity Collada, a bakery displaying a dazzling array of sweets, such as carbayons, an almond pastry, and casadielles, a pastry made with walnut paste. Nibbling on the confections, I stroll to the bus that will take me to Oviedo. Though I intend to return and complete my journey to Santiago de Compostela, for now I’m finding it difficult to turn in my hiking boots and walking stick. It seems that I’ve become a bit addicted to all the sensory stimulation, even the almost daily soaking rain that assures that the Asturian landscape will always be covered in a cloak of green.