More than a few notable people besides Frank Lloyd Wright have called the Chicago suburb of Oak Park home, namely Ernest Hemingway and Betty White. It’s easily accessible from downtown Chicago and contains no less than three historic districts for the historic homes there: Ridgeland, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Seward Gunderson. There has been a continued focus on historic preservation in this community and Wright’s earliest work, including first examples of his prairie style houses, can be found here. We were excited to see the full effect of the man’s vision through his home and studio.

CHICAGO TO KANSAS

Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio

Oak Park, IL 1889

The studio was built shortly after he left Louis Sullivan’s office to start his own practice. Sullivan lent him money to buy the land on which to build the home where he and his first wife raised 6 children. He was fired in 1893 for breaking contract by designing houses on his own, and several of the so called “bootlegs” are nearby. This was where he and his associates developed the Prairie School of architecture for the Midwest, which emphasizes horizontal lines, unbroken panels of windows, sloping roofs, steep overhangs, use of local materials, and integration of the house with the landscape.

He designed ‘paths of discovery” so a handful of turns would need to be made before entering a space. It took 5 to reach this one:

There is a separate entrance for the family:

The children’s playroom was a gymnasium, theatre and concert hall in one.

Because the bathroom window looked onto the playroom, Wright turned the window 90 degrees for privacy.

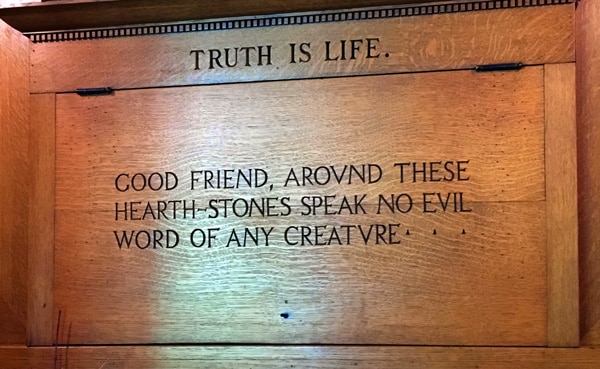

Slogans for the family to live by:

Words on a wall were not enough to keep the Wright family together. In 1909, he turned down a commission to design Henry Ford’s estate, left his family, and sailed for Europe with Mamah Cheney, a client’s wife. Said Wright, “I am leaving the offices to its own devices… deserting my wife and children for one year in search of spiritual adventure…”

Typically egocentric, he claimed he was not influenced at all by anything he saw in Europe. “The Wasmuth Portfolio,” a hundred lithographs of his work, was published in Berlin in 1910. It was a formative influence on European modernist architects such as Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, and Gropius in Berlin, as well as the Austrians, Neutra and Schindler, who defined mid-century modernism in Los Angeles. Upon his return from Europe, Wright reconfigured the home and studio and transformed part of it into a rental to support his family.

Frederick C. Robie House

Chicago, IL 1909

The Robie House is considered the greatest example of the “Prairie style.” When built, it was surrounded by empty parcels of land. Now the 58-ft. long building is engulfed by University of Chicago buildings and looks like a ship moored on dry land. The eastern end formerly looked out to Lake Michigan and to the west, an expanse of prairie grass. The horizontal aspect is emphasized by the matching of the vertical joints of the mortar to the brick, giving the impression that the house was layered, much like a cake. Six-foot-deep eaves, like visors, kept direct sun out. With the fireplaces roaring, and winds off the lake, the house would only manage temperatures in the 50s during winter.

Wright designed the house and interior, the lighting, rugs, furniture and textiles saying, “… it’s impossible to consider the building one thing and the furnishings another.” 175 pieces of custom art glass are yellow when seen from within and multicolored and iridescent from the exterior. With an open floor plan and central hearth, this was loft living in 1909.

The ground floor was used as a corporate venue for the 28-year-old Robie to impress and network. A billiard room was adjacent to the entry and another innovation–a powder room. Things we take for granted today came from the Robie House: radiant heating, a kitchen island wired with electricity, and the first free standing shower made with hardware from Robie’s bicycle company. Shower heads were aimed waist high so to preserve the women’s elaborate hairdos.

The Robies only lived there for 2 years until financial problems forced them to sell. The house survived 3 more tenants, including a white-knuckle stint as a men’s dorm, then faced demolition in 1958 to create student housing for a seminary. Wright joked, “it all goes to show the danger of entrusting anything spiritual to the clergy.” The 90-year-old Wright successfully pleaded for its preservation, convincing his friend, the New York City developer William Zeckendorf, to buy it.

From Chicago we headed out on the open road again, our sense of exploration buoyed by the inspired architecture of a genius. We set the GPS for Wichita, Kansas and reveled in the mythical flatness of the heartland along the drive. The landscape was reduced to the elements of sky, land, and wind, so entirely different from vertical Chicago. A city known for great engineers, it has a rich history of fostering great ideas and the people who make them happen. It’s no surprise then that Frank Lloyd Wright would choose it to leave his indelible “prairie” mark there.

Allen House

Wichita, Kansas 1919

Allen House was built for Henry Allen, a college dropout who went on to become a newspaper publisher, governor of Kansas and US Senator. Wright acknowledges his last brick “prairie” house as one of his finest. He designed it while working on the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo and the L shaped structure, with its enclosed lily pond and garden, has a notable Japanese aesthetic.

It was built for $22,000 with 30 pieces of custom furniture racking up another $7000, making it the most expensive house in Wichita. Radiators are concealed behind the wooden cabinetry. A sofa has cantilevered arms that function as side tables. A recessed light fixture overhead was originally lined with mulberry paper from Japan. The expansive living room is 50 ft. long x 25 ft. wide.

High backed chairs created a room within a room and supported women in tight corsets. The table telescopes to accommodate more and the pattern on a recessed light fixture evokes Kansas wheat.

Wright convinced the Allens that the brick mortar would be more elegant if painted gold. A mixture of brass and copper was actually used and creates a beautiful oxidized glow.

Innovations here included a wall hung water closet, built-in closets in the age of the massive armoire, a security system that is still in use, and a central vacuuming system with ports throughout the house for attaching the hose.

Editor’s Note: Learn the conclusion of Jen’s epic journey in Part 3

Where We Stayed:

The Raphael – The Raphael Hotel is Kansas City’s first boutique hotel and offers exceptional hospitality. Voted by Travel and Leisure’s readers as one of the top 500 of the world’s best, it’s in a beautiful historic property that overlooks Bush Creek and is steps away from Kansas City’s shopping and dining hotspot, the Country Club Plaza. The Raphael’s Chaz on the Plaza is a foodie destination that celebrates cuisine from the heartland.

325 Ward Parkway

Kansas City, MO 64112

816-997-9267