When the topic of Prague comes up, (and even by travel writer standards, it comes up relatively often for me, having spent four months studying abroad there) someone will inevitably make the comment that being in Prague is like walking through a quaint medieval town that’s right out of a fairy tale —and to an extent, they’re right. I totally buy that the majority of people who brave the steep trek up to Prague Castle and pass by the multi-colored Baroque townhouses (Malá Strana, the Lesser Quarter where Prague Castle resides, was founded in 1257, so “medieval” isn’t totally wrong) might feel as though they’ve somehow stumbled into a time machine that’s programmed for—well, for what, exactly? Any one year in time wouldn’t be able to account for all of Prague’s history, nor its mysteries, but most especially, it wouldn’t be able to explain the fairytale quality that draws the kinds of tourists who are simply looking for their happy ending. And while the true history of Prague is far more complex than that, I argue that its inconsistencies and internal conflicts are what make Prague today much more modern than other Eastern European cities.

While it’s impossible to pinpoint a date that Prague’s architectural history really began, a commonly referenced one is July 9, 1357 (at 5:31am, to be exact), which was when the Charles Bridge was officially commissioned by King—who else—Charles IV. As the only route over the Vltava River that connected Prague Castle to Staré Město, the Old Town, until 1841, it’s a major reason why Prague became a central trading post in the centuries that followed. Since its completion in 1402, the bridge has survived many floods, a 71-year repair process (after a 1432 flood in which three pillars were damaged), a battle during the Thirty Years’ War, and more abstractly, arguments among conservationists about whether its many repairs have been in history’s best interest. In fact, none of the thirty statues that line the walkway are the 17th– 18th– century originals (and if you spring for a tour guide during your visit, that’ll be one of the first things they tell you). Since the 1960s, they’ve all been ousted by replicas while the originals sit peacefully in the National Museum, where there is far less threat of natural damage due to weather or, say, the unpredictable antics of obnoxious tourists. Today, a visit to the Charles Bridge will likely incorporate obliging to take photographs of vacationing families or happy couples, shopping for jewelry or crafts from local vendors who’ve been selected to set up shop there, and of course, pushing through crowds. It’s still worth the trip, however, if only just to say you’ve walked across a medieval bridge, or to gawk at the Old Town bridge tower, a gorgeous gothic feat that anchors the east end of the bridge.

Stroll past it to Old Town Square, the heart of Prague (well, at least according to every travel guide) and you’ll notice a large mass of people facing the exact same direction and standing curiously still. As the top of the hour approaches, the crowd gets bigger, until the clock strikes and everyone lifts their iPhones to capture the dancing figurines that pop out of the sides. This is the Orloj, the oldest working astronomical clock in the world. Visitors couldn’t miss it, even if they wanted to—but then again, why would you? Constructed in 1410, the Orloj is the beating pulse of Old Town Square, well deserving of its towering spot atop the masses.

East of the square, bars and restaurants that boast “authentic Czech cuisine” populate the winding cobblestone streets, hoping to capture the wandering tourist. Old Town is perhaps a misnomer; most of the people here are new. But what’s more ironic is that the Old Town contains one of the most intriguing works of modern architecture in the world. The House of the Black Madonna by Josef Gočár is one of the only cubist buildings ever designed, but unfortunately, the museum for Czech cubist art that once occupied the top three floors has recently closed, and visitors now must enjoy the striking work from the outside.

Back towards the river, south of the Charles Bridge lies the famous Dancing House, nicknamed Fred and Ginger by its architect, Frank Gehry for the way it resembles a pair of dancers. While today it is home to investors, real estate companies, and other international businesses, the Dancing House is quintessential Prague—not only because of its historic location (the site had been bombed in 1945, and decades later, the future president of Czechoslovakia and dissident hero, Václav Havel lived in the neighborhood)—but since its completion in 1996, the deconstructivist masterpiece has come to symbolize the modernization and innovation of post-communist Prague.

Across the Vltava and a taxi ride away past the castle, you’ll notice what appears to be just another nondescript communist style building, but upon further inspection—if you’re either an architecture enthusiast or you’ve done your travel homework—you might recognize it as the Müller House, a modernist building from the 1930s, designed to maximize functionality by drawing from concepts of space rather than sections or floors. Unlike the House of the Black Madonna, visitors are allowed to roam through its interior, which acts as an outpost of the City of Prague Museum.

While the National Museum (the massive building at the top of Wenceslas Square) is currently closed for renovations, art hounds can get their fix at the delightful Trade Fair Palace, or Veletržní Palác, which features the largest collection of all the museums operated by the National Gallery. Off the typical tourist track in terms of geography, the museum is well-worth the trip to the up and coming neighborhood of Holešovice. Here, spectators can gaze upon 2,000 works from the 19th, 20th and 21st century by Czech legends such as Alfons Mucha (including The Slav Epic), as well as international masters like Picasso, Van Gogh, Renoir, and more. The building itself is an example of early Functionalist design—visitors will get the sense that they are in a long, thin rectangle when in fact the galleries expand for what feels like miles.

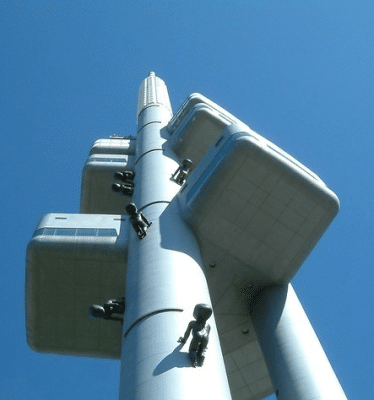

Though Prague’s architecture is more diverse and storied than perhaps any other European city, not all of its structures are universally loved. Take, for instance, the polarizing contemporary artist David Černý, who in 2000 installed a number of babies that appear to be crawling up the Žižkov television tower (Tower Babies). Having looked at it every day for four months, I grew to appreciate the odd-looking sculptures, however fundamentally bizarre they are. The most unconventional part of the structure will always be the tower itself, which, like many of Prague’s buildings, is an example of communist-era design, to which Černý’s babies only add intrigue.

The Czechs today may still seem just a bit rankled by communism and the Soviet occupation and even young people born after the Velvet Revolution in 1989 share the same cynicism as their elders. This attitude equates to a cultural honesty that Americans will appreciate (an oft-quoted example of the phenomenon is when you ask someone in Prague “how are you?” you’ll get a truthful answer rather than the typical American one, …“fine!”). And no contemporary artist captures this quality better than Černý, who, regardless of the controversy that surrounds nearly every one of his works, is by far the best-known (and perhaps, loudest) voice for the alternative side of Prague’s cultural goldmine. One of his pieces last October floated a giant purple middle finger on a barge down the Vltava that faced Prague Castle, the residence of recently elected President Miloš Zeman, who (among popular opinion, including Černý’s) is too close to the Communist party. While newspapers and websites all over the world wrote about the story, the Czechs’ reaction was more or less a collective shrug.

The Czech view of the world is just one of the reasons why I pause before agreeing with tourists who gush over Prague’s magical, fairytale-like aura. To me, Prague isn’t a city that’s been miraculously preserved in time (although much of its architecture has, indeed), but instead the beautiful culmination of competing trajectories. For in a fairytale, who would build sculptures like Černý’s? No one would, which is why Prague, for all its quaintness on the outside, is a complicated jumble under the surface. And thank goodness for that—nothing great ever comes out of complacency.

https://travelsquire.com/ts/czech-republic/stories/

The country code for Prague is 420.

Where to Stay:

Hotel Residence Agnes – Located a short distance from the Dlouhá třída tram stop allowing for easy access to Václavské náměstí (Wenceslas Square). Contact: Haštalská 943/19, Praha 1, Czech Republic +420-222-312-417, www.residenceagnes.cz

Hotel General – Found on the west bank of the Vltava River, the hotel is minutes away from the Anděl metro and Zborovská tram stop. Contact: Svornosti 1143/10, Praha Smíchov, Czech Republic +420-257-318-320, www.hotel-general.com

Hotel Paris – Within walking distance of the Palladium Shopping Center and the Náměstí Republiky metro and tram stops. Contact: U Obecního domu 1, Praha 1, Czech Republic +420-222-195-195, www.hotel-paris.cz

Where to Eat:

Bellevue – Situated along the east bank of the Vltava River, the restaurant is right off the Karlovy láznĕ tram stop and allows patrons to easily visit the Charles Bridge after dinner. Contact: Smetanovo nábřeží 329/18, Praha-Staré Město, Czech Republic +420-222-221-443, www.bellevuerestaurant.cz

Terasa U Zlaté Studnĕ – Feel like a royal as you eat at this restaurant near Prague Castle. It can be reached by way of the Malostranska metro stop or the Malostranské náměsti tram stop. Contact: U Zlaté studnĕ 166/4, Praha, Czech Republic +420-257-533-322, www.terasauzlatestudne.cz

Café Colore – Head over to this café after wandering around Václavské náměstí or take the metro to Mustek or the tram to Vodičkova or Národní třída to reach it. Contact: Palackého 740/1, Praha 1-Nové Mĕsto, Czech Republic +420-222-518-816, www.cafecolore.cz

Where to Shop:

Globe Bookstore & Café – Get quick bite to eat or find a good book at Prague’s first English language bookstore located steps away from the Myslíkova tram stop. Contact: Pštrossova 6, Praha 1, Czech Republic +420-224-934-203, www.globebookstore.cz

Palladium Shopping Center – Located in the heart of Náměstí Republiky, this shopping center always the avid shopper to easily reach it by either metro or tram. Contact: Náměstí Republiky 1, Praha 1, Czech Republic +420-225-770-250, www.palladiumpraha.cz/en

Antique Ahasver – Find this great antique store by taking the tram to either Malostranské náměstí or Hellichova. Contact: Prokopská 625/3, Praha 1-Malá Strana, Czech Republic +420-257-531-404

Sephora – Do some luxury shopping by taking the tram to Václavské náměstí or the metro to Můstek or Muzeum. Contact: Václavské náměstí 19, Praha 1, Czech Republic 222–314–889, www.sephora.cz