Since the 10th century, the Jewish community of Prague has not only survived, but also thrived. Enduring early prejudice and pogroms, Prague’s Jewish Town was at the center of a dazzling 16th century renaissance. The community attracted some of Europe’s most famous rabbis, scholars and mystics as well as mathematicians, scientists and astronomers, artists, poets, and philosophers. Grand synagogues and community buildings rose, filled with splendidly crafted art and artifacts. Prague’s Jewish Town was so highly respected that its mayor, Mordechai Maisel, was appointed chief finance minister of the Holy Roman Empire.

By the 18th century, there were more Jews in Prague than anywhere else in Europe. Two centuries later, the Nazis had liquidated 90,000 Jews in the Czech lands of Bohemia and Moravia, but they could not destroy the status of Prague’s Jewish Town. In a strange quirk of fate, Nazi attempts to dispel the Jewish presence in the Czech lands backfired, assuring the survival of the community and its culture.

Today, visitors to Prague can continue to experience much of the Jewish Town’s early magnificence. Just northwest of the Old Town Square, at a bend in the Vlatava River, is Josefov, the name the Jewish Town acquired after Emperor Joseph II’s 1782 edict granting Jews wide-ranging economic and civil rights. The jewel in Josefov’s crown is the Jewish Museum in Prague, which includes four treasure-filled historic synagogues as well as Europe’s oldest Jewish cemetery.

The museum’s synagogues, architecturally significant in their own right, are treasure troves of religious objects, including ornately carved Torah pointers, gleaming seder plates, books, and household items, and not all of the treasures are from Prague. When Hitler destroyed synagogues in Bohemia and Moravia, he ordered thousands of objects sent to Prague, where many historians believe he intended to set up “An Exotic Museum of an Extinct Jewish Race.” Against all odds, Jews survived the Holocaust, and these objects, stored in Prague’s synagogues and storehouses, continue to comprise one of the richest caches of Jewish cultural artifacts anywhere in the world.

The first of the Jewish artifacts’ holding sites is Maisel Synagogue, which was built by the Jewish Town’s mayor and master builder Mordechai Maisel and is maintained today by the Jewish Museum. Originally built in neo-Gothic style, it was destroyed by fire in 1689 and rebuilt in the Baroque style. It houses the first part of one of the museum’s permanent exhibits, entitled “History of the Jews in Bohemia and Moravia: From First Settlements to the Beginning of Emancipation,” a treasury of silver ceremonial objects, handsomely embroidered Torah covers, and rare books and manuscripts from the 14th to 18th centuries.

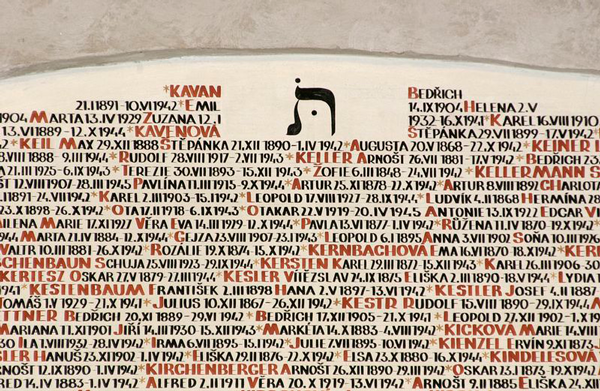

A short walk away, on Široká Street, the Pinkas Synagogue also illustrates the endurance of Prague’s Jewish community. Originally constructed in the Renaissance style as a family’s private house of worship, the walls of the small beige-colored synagogue are inscribed with the names of nearly 80,000 victims from Prague and the surrounding Czech lands who perished during the Holocaust. The walls were erased during Czechoslavakia’s Communist regime, begun in 1948, but were restored after the 1989 revolution. When Vlatava River floods destroyed the walls in 2002, the community restored them once again. Also in the Pinkas Synagogue is a heart-wrenching exhibit of art works by children who perished in the Terezín concentration camp.

Nearby is the entrance to the Old Jewish Cemetery, Europe’s oldest Jewish burial ground and the resting place of some of the Jewish Town’s most illustrious citizens. Used from the early 15th century until 1787, the small plot of land contains at least 100,000 graves, many layered 12 deep. Each time the cemetery ran out of room, more earth was brought in to cover existing graves, and new graves were dug atop them with new headstones set alongside older ones. Today, some 12,000 mossy headstones rise higgledy-piggledy from the earth, slanting in different directions like waves in a restless sea of humanity.

The cemetery’s most famous grave is that of Judah Loew ben Bezalel, one of Prague’s foremost rabbis. His resting place is marked by a large monument with a heraldic shield of a lion with two intertwined tails, believed to represent both the rabbi’s name “loew,” meaning lion in German, and the two-tailed lion of Bohemia’s coat of arms. Also interred here is Mordechai Maisel himself, who helped bankroll the Austrian government’s campaign against the Turks during the Thirty Years’ War. Here, too, lies David Gans, a renowned Renaissance historian, mathematician, and astronomer. The cemetery’s oldest grave, dated to 1439, is that of rabbi, scholar, and poet Avigdor Karo. Among his many writings is an elegy to 3,000 Jews murdered in the Jewish Town during Passover 1389, a document still read by Prague’s Jews on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement.

Not far from the cemetery is the venerable Klausen Synagogue. Built in Baroque style with funds donated by Mayor Mordechai Maisel, it was constructed to honor the Emperor Maximilian II during his visit to the ghetto in 1573. Once the Josefov’s largest synagogue, its main nave now houses the first part of the Jewish Museum’s “Jewish Customs and Traditions” permanent exhibit, including textiles and objects relating to birth, circumcision, bar mitzvah, marriage, and divorce.

A short walk north is yet another building included in the Jewish Museum in Prague. The pseudo-Romanesque Ceremonial Hall, built in 1911, was the meeting place of the Prague Burial Society, which oversaw proper Jewish burials. Today, the hall hosts the second part of the “Jewish Customs and Traditions” exhibit, focusing on illness and death. Displays include the ritual washing of the dead, the Jewish burial ceremony and prayers for the dead. In addition to fragments of 14th-century tombstones, there’s also a wealth of engravings and paintings depicting the Old Jewish cemetery.

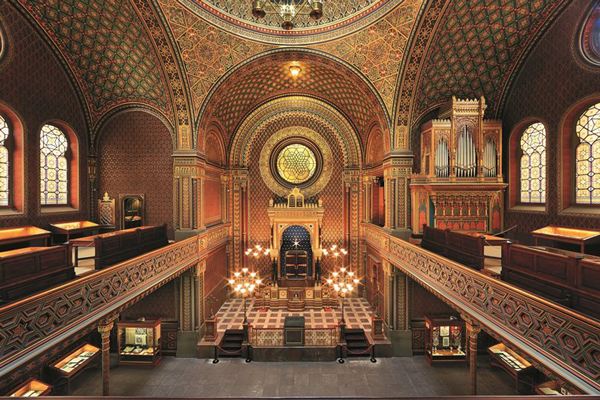

A few blocks east is the Jewish Museum’s fourth synagogue, the Spanish synagogue, a striking yellow-and-white building built in 1868. Outside, the synagogue is a Moorish fantasy of arched windows and domed turrets. Inside, it features dazzling Islamic-style tiles and stained-glass windows. Aside from its architecture, one of the synagogue’s claims to fame is that František Škroup, composer of the melody used for the Czech National Anthem, was one of its former organists. Today, the synagogue houses the second part of the permanent “History of the Jews in Bohemia and Moravia: From Emancipation to the Present” exhibit as well as a dazzling display of silver religious objects in its upper-floor prayer hall.

In the middle of the synagogue cluster is the Old-New Synagogue, or Altneuschul. Though not part of the Jewish Museum in Prague, it is Europe’s oldest existing synagogue and the Jewish Town’s oldest site. Still used for services, it has been in operation almost continuously for 700 years, except during the 1941-1945 Nazi occupation. Among its worshippers was the writer Franz Kafka, whose bar mitzvah was held there in the late 19th century.

Known as the “New” or “Great” shul until other synagogues were built in the 16th century, the Old-New Synagogue was constructed in the late 13th century by masons from the Royal Workshop who also were building the nearby Convent of St. Agnes, a clue to the high esteem in which many emperors of the Holy Roman Empire held Prague’s Jews. Architecturally speaking, the synagogue, a rectangular structure with a large saddle roof and Gothic gables, is also the oldest surviving synagogue with a medieval double-nave. Inside, two large octagonal pillars hold up a vaulted ceiling lit by numerous brass chandeliers. Twelve narrow pointed windows represent the 12 Tribes of Israel.

Aside from its architectural and historical significance, the Old-New Synagogue is a repository for the Jewish Town’s most enduring legends. Though the building’s stone foundation officially dates back to 1270, legend has it that the foundation stones were brought there by angels from the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. When the Temple is restored, the story goes, the stones must be returned. Another legend states that the synagogue has been protected against fire over the centuries by the wings of angels transformed into doves.

But the most famous tale is the legend of the Golem. It’s believed that the Golem, the powerful being that Rabbi Loew created from clay from the Vltava River to protect Prague’s Jews from pogroms and prejudice, still resides in the Old-New Synagogue’s attic. Should Prague’s Jewish community ever need the Golem’s protection in the future, it stands ready and willing to help. But, given the community’s remarkable history of survival, it’s doubtful that the Jews of Prague will ever need the Golem again.

https://travelsquire.com/ts/czech-republic/stories/

[alert type=white]

What to See:

The Jewish Museum in Prague—It comprises four treasure-filled synagogues—the Klausen, Maisel, Pinkas and Spanish synagogues—along with the Ceremonial Hall, and the Old Jewish Cemetery, Europe’s oldest. Also part of the complex is the modern Robert Guttmann Gallery, displaying works by Czech Jewish artists from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as well as a Reservation Centre for tickets and information. www.jewishmuseum.cz

The Old-New Synagogue —Europe’s oldest existing synagogue and the oldest site in Prague’s Jewish Town, the Altneuschul is still used for services. Maiselova 18, Prague 1, 224-800-812. www.synagogue.cz/

[/alert]